Habitat: Red Sea Urchins can be found on both rocky shorelines where there is a lot of wave action and on quite shores. They live in the low intertidal zone to 91 meters deep. In the Pacific Northwest you would more likely find the Green and Purple Sea Urchins in the low intertidal area than the larger Red Sea Urchin; they are generally found in deeper water.

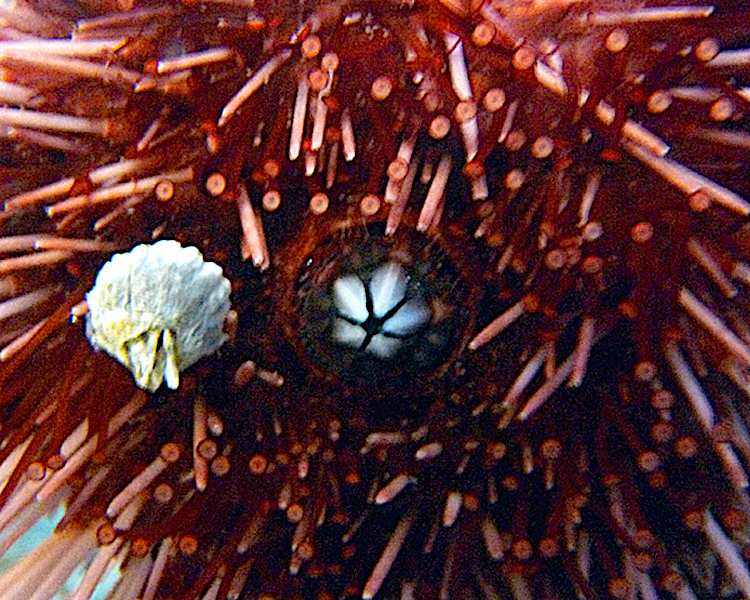

Food: All sea urchins eat seaweed. The Red Sea Urchins prefer to eat kelp (brown seaweed) and red seaweed, however in our aquarium they have been observed eating a diversity of things including Eel Grass (Zostera marina). On one occasion a Bay Pipefish (Syngnathus leptorhynchus) was captured by the tube feet of our Red Sea Urchin and eventually eaten. Sea Urchins use their tube feet to pass the food that they find into their jaws, where their 5 teeth (Aristotle’s lantern) chew the food as they take it into their mouth and digestive tract.

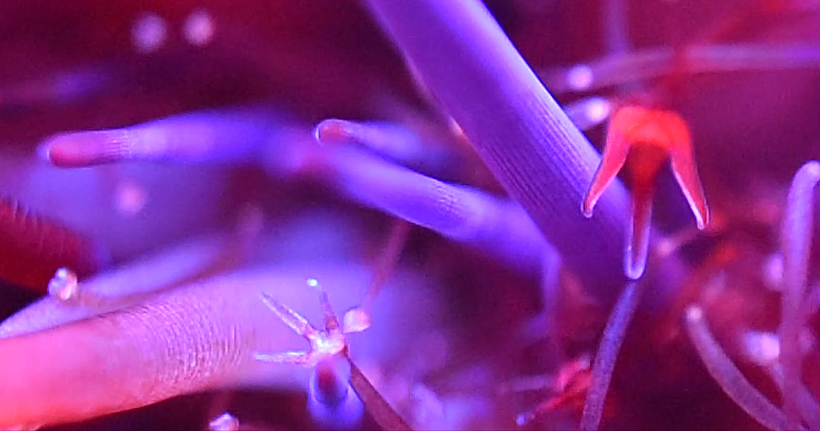

A close up showing the purple spines, red tube feet and the very tiny looking tube feet with claws at the end are the defensive pedicellariae.

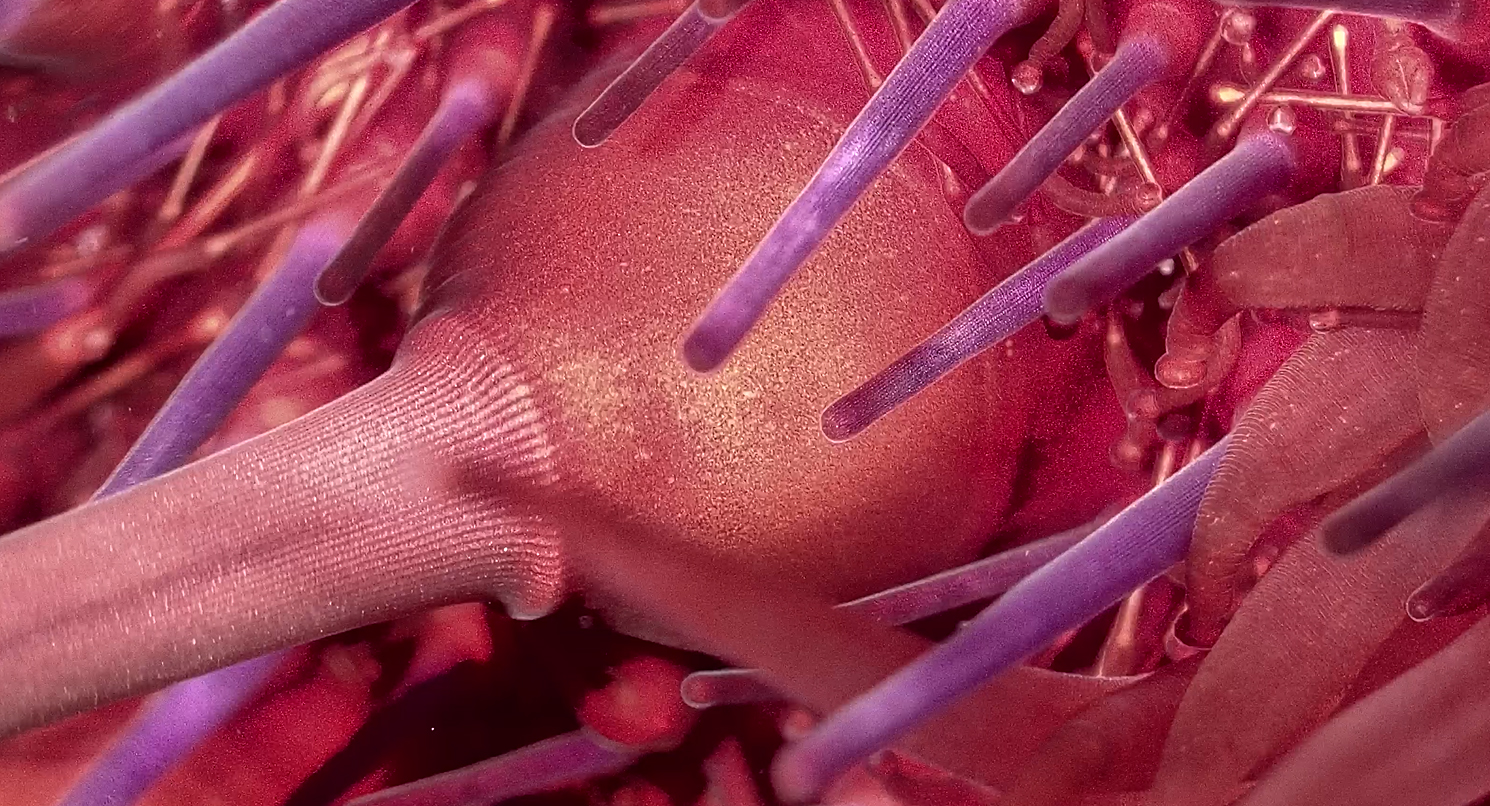

Pedicellariae (claw-like defensive structures), tube feet and spines.

The base of a large spine, small spines, tube feet, and pedicellariae (top right).

The 5 teeth of the Aristotle’s Lantern can be seen on the underside of a sea urchin.

Predators: The hard test and spines give the Red Sea Urchin some protection from its predators but they aren’t venomous. The main predators of this species include sea stars, sea otters, octopus, crabs, and wolf eels. In Japan, people eat the Red Sea Urchin’s reproductive organs as a delicacy.

In addition to the spines sea urchins and sea stars also have defensive structures called pedicellaria. These modified tube feet have claw-like structures at their ends that will grab onto anything attacking including plankton, such as barnacle larvae. Once they latch on they don’t release. Each species may have a number of different types of pedicellaria that have different functions.

Life Cycle: Red Sea Urchins fertilize in water column. After a period the fertilized eggs develop into larvae. It takes 6 to 8 weeks for the larvae to develop into juvenile sea urchins. Adult urchins can live up to be 7 to 10 years old.

Photos by D. Young

References:

CA Marine Species Portal. (n.d.). CA Marine Species Portal. Retrieved July 31, 2024, from https://marinespecies.wildlife.ca.gov/red-sea-urchin/the-species/

Kozloff, N. (1993). Seashore of the Northern Pacific Coast. New York: Vail – Ballou Press.

Lamb, A. and Handby, B. (2005). Marine Life of Pacific Northwest: a photographic encyclopedia of invertebrates, seaweeds and selected fishes. Madeira Park, BC.: Harbour Publishing.

Red Sea Urchin. Species and Habitat Outlines. Retrieved January 21, 2010 from http://www.shim.bc.ca/species/rurchin.htm

Sept, J.D. (1999). The Beachcomber’s guide to Seashore Life in the Pacific Northwest. Madeira Park, BC.: Harbour Publishing.