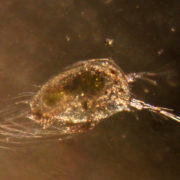

Opossum Shrimp Common Names: Mysid Shrimp, Opossum Shrimp Scientific name: (Order) Mysida Size range: 5-25mm long (mature length) Identifying Features Mysida is an order of over 1000 species of similar shrimp-like crustaceans. The creatures get their name from the presence of a ‘brood pouch’ – an egg chamber attached to the female. This pouch gives the female Mysida a distinctive ‘bulge’, allowing them to be easily identified. While there are many types of Mysida that are pale, and even transparent, there are also varieties that have bold orange and brown colourations. Additional features include compound eyes protruding from stalks, and a rigid carapace that covers the creature’s head and the thorax. While very similar in appearance to shrimp, Mysida don’t have free-swimming larvae, and are hence classified differently. Habitat Mysids can be found living in both freshwater and salt-water environments. The majority of these creatures are free-living, and survive as independent organisms; however, there are some mysids that have been noted to develop commensal relationships with other animals such as sea anemones and hermit crabs. Mysids are usually observed occupying low-light areas at the bottom of lakes during the day. They then migrate upwards at night to food on zooplankton and phytoplankton. In the ocean, mysids can be found as both near the surface, near the ocean floor, and everywhere in between. Some species may burrow themselves into the sand during a low tide. Food (Prey) Most Opossum shrimps are generally regarded as omnivorous and feed mainly on algae, detritus, and zooplankton. Pelagic Mysida filter particles as they swim, while benthic species consume small particles they gather from combing their body and legs. Other species even favour a nearly entirely carnivorous diet. These Mysida will scavenge and feed on the remains of copepods, amphipods, zooplankton, and even other Mysids. In fact, it’s not unusual for parent mysids to eat some of their own young if they have to! Predators Mysids are very abundant in population and reproduce quickly. This has resulted in them being the ideal prey for a whole host of creatures and perfect for culturing by humans. Baleen whales, cephalopods, small fish, shrimp, rays, rockhopper penguins, rockfish and seahorses all have mysids as a significant part of their diets. Mysids are one of the most commonly human-cultured foods for use in commercial farms and aquariums. Mysids are fed to farmed shrimp, cephalopods, fish larvae, and many juvenile sea creatures that are otherwise difficult to nurture. Life Cycle and Reproduction Juvenile mysids are very similar in appearance to their adult counterparts, but are smaller in size (typically less than 10mm). The length of the adult female’s body is a good indicator of brood size. The larger the creature the more eggs, and hence, the more offspring it is capable of having. In most species, the male develops an elongated limb-like organ that is used to transfer sperm to the female. There are, however, some species that release sperm directly into the water around them. The female then uses her thoracic legs to create a current that directs the sperm towards her. A mysid will usually take between 13 and 20 days to reach full size, but anywhere between 6 weeks and two years to reach sexual maturity. The factors that affect the rate of development are primarily water temperature and food availability. Although mysids generally have smaller number of offspring, they have a short reproduction cycle of only 4-7 days. This allows them to quickly generate a massive population. Video by Conor Graff

References Yerman, M.N. & Lowry, J.K. Division of Invertebrate Zoology. Retrieved January 22/2013 from http://crustacea.net/ Marini, Frank Ph.D., Moe, Martin. Retrieved January 21/2013 fromhttp://www.advancedaquarist.com/ Mees, J. (2013). Retrieved January 22/2013 from http://www.marinespecies.org/ Patterson, Heather Michelle B.Sc., University of Victoria, 1996. Retrieved January 2013 from http://www.geog.uvic.ca Brusca, R.C. and G.J. Brusca. 2003. Invertebrates, 2nd edition. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Massachusetts. Retrieved January 22/2013 from http://eol.org/ Todd, C.D., Laverack, M.S. & Boxshall, G.A.. Coastal Marine Zooplankton (second edition) – 1996. Lamb, Andy and Hanbe, Bernard P. (2005) Marine Life of the Pacific Northwest. a photographic encyclopedia of invertabrates, seaweeds and selected fishes. Madeira Park, BC, V0N 2H0: Harbour publishing co, Ltd.

Author: Jamie Lenihan

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!